Export the dataframe

In the previous section, we explored some face tracking data using the dataframe view. In this section, we will see how we can use the dataframe API of the Rerun SDK to export the same data into a Pandas dataframe to further inspect and process it.

Load the recording load-the-recording

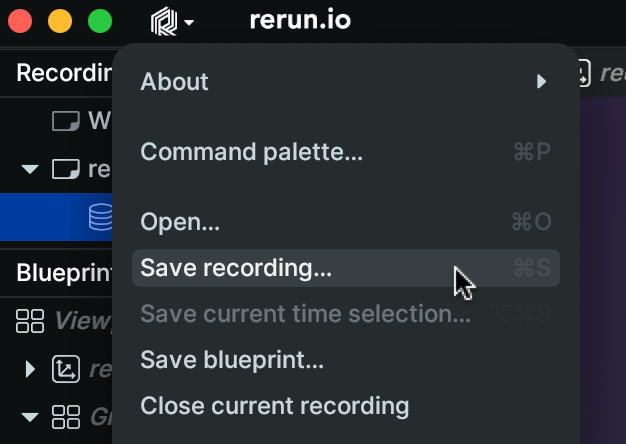

The dataframe SDK loads data from an .RRD file. The first step is thus to save the recording as RRD, which can be done from the Rerun menu:

We can then load the recording in a Python script as follows:

First perform the necessary imports,

from __future__ import annotations

from pathlib import Path

import numpy as np

import rerun as rr

then launch the server to load the recording

server = rr.server.Server(datasets={"tutorial": [example_rrd]})

client = rr.catalog.CatalogClient(server.url())Query the data query-the-data

Once we loaded a recording, we can query it to extract some data. Here is how it is done:

dataset = client.get_dataset("tutorial")

df = dataset.filter_contents("/blendshapes/0/jawOpen").reader(index="frame_nr")A lot is happening here, let's go step by step:

- We first create a view into the recording. The view specifies which content we want to use (in this case the

"/blendshapes/0/jawOpen"entity). The view defines a subset of all the data contained in the recording where each row has a unique value for the index. - In order to perform queries a view must become a dataframe. We use the

reader()call to specify this transformation where we specify our index (timeline) of interest. - The object returned by

reader()is adatafusion.Dataframe.

DataFusion provides a pythonic dataframe interface to your data as well as SQL querying.

Create a Pandas dataframe create-a-pandas-dataframe

Before exploring the data further, let's convert the table to a Pandas dataframe:

pd_df = df.to_pandas()Inspect the dataframe inspect-the-dataframe

Let's have a first look at this dataframe:

print(df)Here is the result:

frame_nr frame_time log_tick log_time /blendshapes/0/jawOpen:Scalars:scalars

0 0 1970-01-01 00:00:00.000 34 2024-10-13 08:26:46.819571 [0.03306490555405617]

1 1 1970-01-01 00:00:00.040 92 2024-10-13 08:26:46.866358 [0.03812221810221672]

2 2 1970-01-01 00:00:00.080 150 2024-10-13 08:26:46.899699 [0.027743922546505928]

3 3 1970-01-01 00:00:00.120 208 2024-10-13 08:26:46.934704 [0.024137917906045914]

4 4 1970-01-01 00:00:00.160 266 2024-10-13 08:26:46.967762 [0.022867577150464058]

.. ... ... ... ... ...

409 409 1970-01-01 00:00:16.360 21903 2024-10-13 08:27:01.619732 [0.07283800840377808]

410 410 1970-01-01 00:00:16.400 21961 2024-10-13 08:27:01.656455 [0.07037288695573807]

411 411 1970-01-01 00:00:16.440 22019 2024-10-13 08:27:01.689784 [0.07556036114692688]

412 412 1970-01-01 00:00:16.480 22077 2024-10-13 08:27:01.722971 [0.06996039301156998]

413 413 1970-01-01 00:00:16.520 22135 2024-10-13 08:27:01.757358 [0.07366073131561279]

[414 rows x 5 columns]We can make several observations from this output:

- The first four columns are timeline columns. These are the various timelines the data is logged to in this recording.

- The last column is named

/blendshapes/0/jawOpen:Scalars:scalars. This is what we call a component column, and it corresponds to the Scalar component logged to the/blendshapes/0/jawOpenentity. - Each row in the

/blendshapes/0/jawOpen:Scalarcolumn consists of a list of (typically one) scalar.

This last point may come as a surprise but is a consequence of Rerun's data model where components are always stored as arrays. This enables, for example, to log an entire point cloud using the Points3D archetype under a single entity and at a single timestamp.

Let's explore this further, recalling that, in our recording, no face was detected at around frame #170:

print(pd_df["/blendshapes/0/jawOpen:Scalars:scalars"][160:180])Here is the result:

160 [0.0397215373814106]

161 [0.037685077637434006]

162 [0.0402931347489357]

163 [0.04329492896795273]

164 [0.0394592322409153]

165 [0.020853394642472267]

166 []

167 []

168 []

169 []

170 []

171 []

172 []

173 []

174 []

175 []

176 []

177 []

178 []

179 []

Name: /blendshapes/0/jawOpen:Scalars:scalars, dtype: objectWe note that the data contains empty lists when no face is detected. When the blendshapes entities are Cleared, this happens for the corresponding timestamps and all further timestamps until a new value is logged.

While this data representation is in general useful, a flat floating point representation with NaN for missing values is typically more convenient for scalar data. This is achieved using the explode() method:

pd_df["jawOpen"] = pd_df["/blendshapes/0/jawOpen:Scalars:scalars"].explode().astype(float)

print(pd_df["jawOpen"][160:180])Here is the result:

160 0.039722

161 0.037685

162 0.040293

163 0.043295

164 0.039459

165 0.020853

166 NaN

167 NaN

168 NaN

169 NaN

170 NaN

171 NaN

172 NaN

173 NaN

174 NaN

175 NaN

176 NaN

177 NaN

178 NaN

179 NaN

Name: jawOpen, dtype: float64This confirms that the newly created "jawOpen" column now contains regular, 64-bit float numbers, and missing values are represented by NaNs.

Note: should you want to filter out the NaNs, you may use the dropna() method.

Next steps next-steps

With this, we are ready to analyze the data and log back the result to the Rerun viewer, which is covered in the next section of this guide.